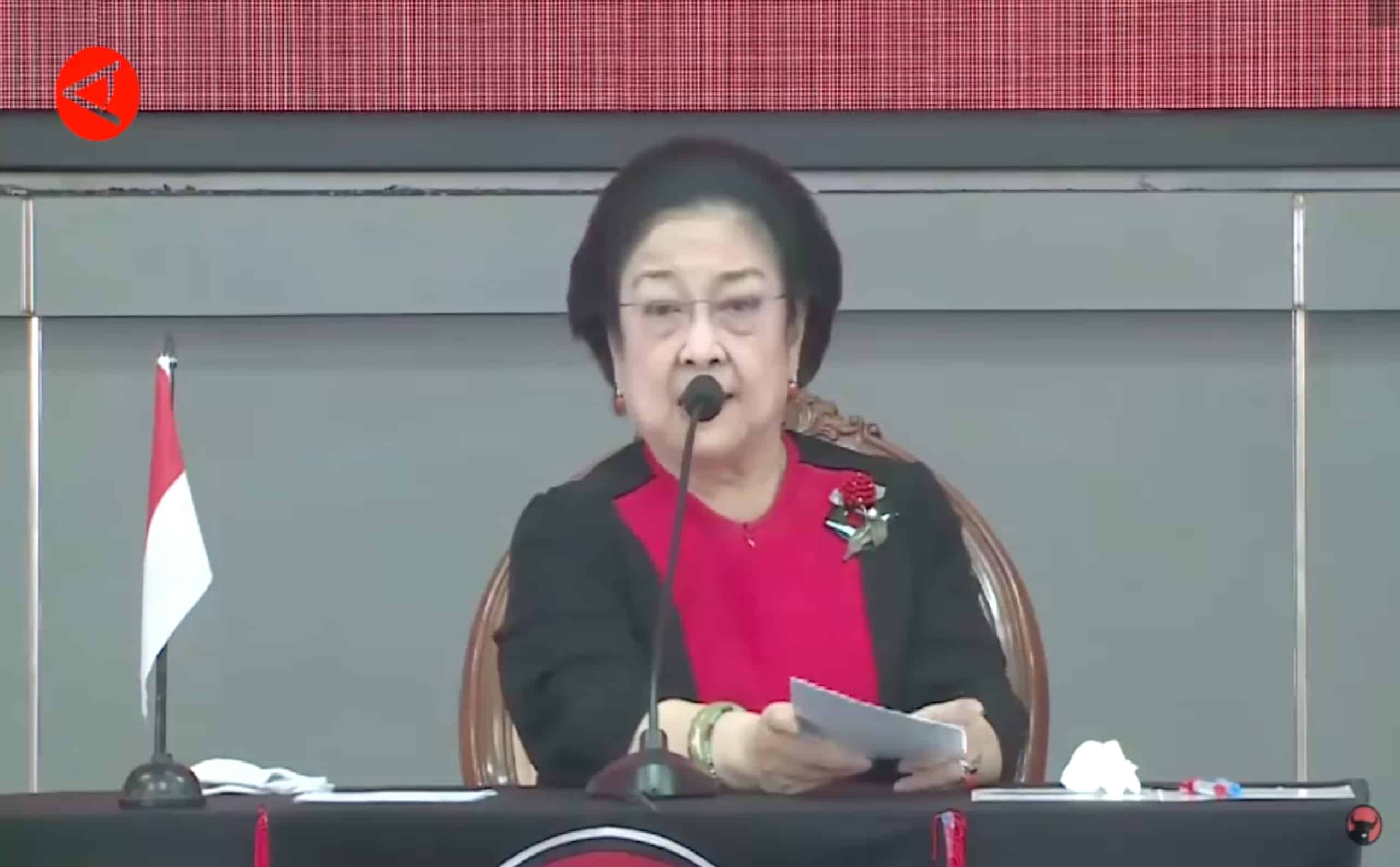

Megawati Soekarnoputri speaking at the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) National Meeting on 21 June. Image from PDI-P/Antara.

Former President Megawati Soekarnoputri, the long-serving chair of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), has been widely criticised for comments she made at her party’s 2022 National Meeting on 21 June.

At the event, Megawati told the audience how she had warned her children, including Puan Maharani, not to bring home a meatball soup seller (tukang bakso) as a prospective partner, prompting laughs from members of the audience, including Puan and President Joko Widodo. Megawati then went on to say that she was glad that black West Papuans were starting to intermarry with migrants — like coffee with milk (kopi susu) — therefore becoming more Indonesian.

These disgraceful comments should never have been made. But, in a way, I am glad they were, because they provided a clear view of what political elites really think about the masses, the tukang bakso of the world, and West Papuans.

Implied in Megawati’s comments was the old Javanese concept of bibit bobot bebet – the idea of marrying up to make better connections politically, and at the same time, improving one’s genes (described by Megawati as rekayasa genetika, genetic manipulation).

By using the phrase kopi susu she was implying that the sweetness and whiteness of milk will dilute the bitterness and blackness of coffee. Mixing with transmigrants will supposedly dilute the blackness of West Papuans, making them more Indonesian than they currently are. In fact, she claimed that through “blending”, West Papuans were becoming more Indonesian (the literal translation of her words was “very Indonesian” – Indonesia banget).

Intentionally or not, Megawati was basically describing ethnic replacement and eugenics, with her statement revealing racist colonial ideas about Papua that hide just beneath the surface in the thinking of many in the political elite.

When Megawati’s statements were criticised as racist, some prominent figures came to her defence, brushing off her comments as a light-hearted joke. These responses too, should be called out for what they were: gaslighting – a strategy designed to justify the laughter of the audience and, at the same time, invalidate the emotions triggered in the subjects of the “joke”.

Jokes do not exist in a vacuum, they exist in political and historical spaces that provide context. For Megawati’s statements to trigger laughter in the way they did, her audience would have to share the same understanding of tukang bakso and West Papuans, and the class and racial differences between them and the privileged (and apparently superior) Megawati and Puan.

To be able to laugh along, the audience must associate themselves with Megawati and Puan and hence share their privilege. It is telling that the only people defending Megawati’s joke and claiming critics were too sensitive were also elite members of the majority.

There are many different types of laughter. For example, we might laugh at ourselves when we do something silly. Friends might laugh at each other, too, but this requires both parties to perceive themselves as equals. A third type of laughter common in Indonesia is gallows humour – laughing at a harsh reality as a coping mechanism. One such example is mop Papua, in which Papuans make fun of their experiences of racism and violent encounters with development projects to cope with the grim reality thrust upon them.

Another, more spiteful, kind of laughter involves laughing at “the other”. Megawati and her peers ‘othered’ tukang bakso and West Papuans because of their class and race, respectively. Tukang bakso represent the urban poor and marginalised, the people who work in the informal sector. They are often depicted as villagers who have migrated to the city for a better life. Despite forming the backbone of Indonesia’s economy, workers in the informal sector are still looked down upon by the privileged.

West Papuans, meanwhile, are often depicted simply as savages who need to be saved or erased, depending on how the political winds are blowing.

One of the saddest aspects of Megawati’s “joke” was who was laughing: Megawati, Puan, Jokowi and senior PDI-P members. As children of presidents, Megawati and Puan are both members of the elite, but their party always seeks votes by claiming to represent the little people (wong cilik). Likewise, Jokowi, the current president, likes to present himself as a commoner in his interactions with the people, but is now firmly part of the elite.

Sadder still, these powerful individuals are precisely the people who have the power to do something about the political and economic reality that tukang bakso and West Papuans face. Their laughter seemed to justify, or at least trivialise, the widespread lack of opportunities for decent work that leads many poor people to migrate to urban centres, and the massacres, land grabbing, settler migration, and failure to provide basic health care in Papua.

Hopefully those who made the “joke”, laughed at the joke, defended the joke, sought to normalise the joke, or gaslit the victims of the joke, are offended by being called racist and classist. Hopefully they do not stop at taking offence and feeling anger. Hopefully they sit with their feelings of offence and anger, reflect on why they feel offended, and try to look at the situation from the point of view of the subjects of the joke.

Unfortunately, Megawati’s “joke” suggests it may be a long time before many in the elite really understand that jokes about race and class can never be innocent.